Obituary

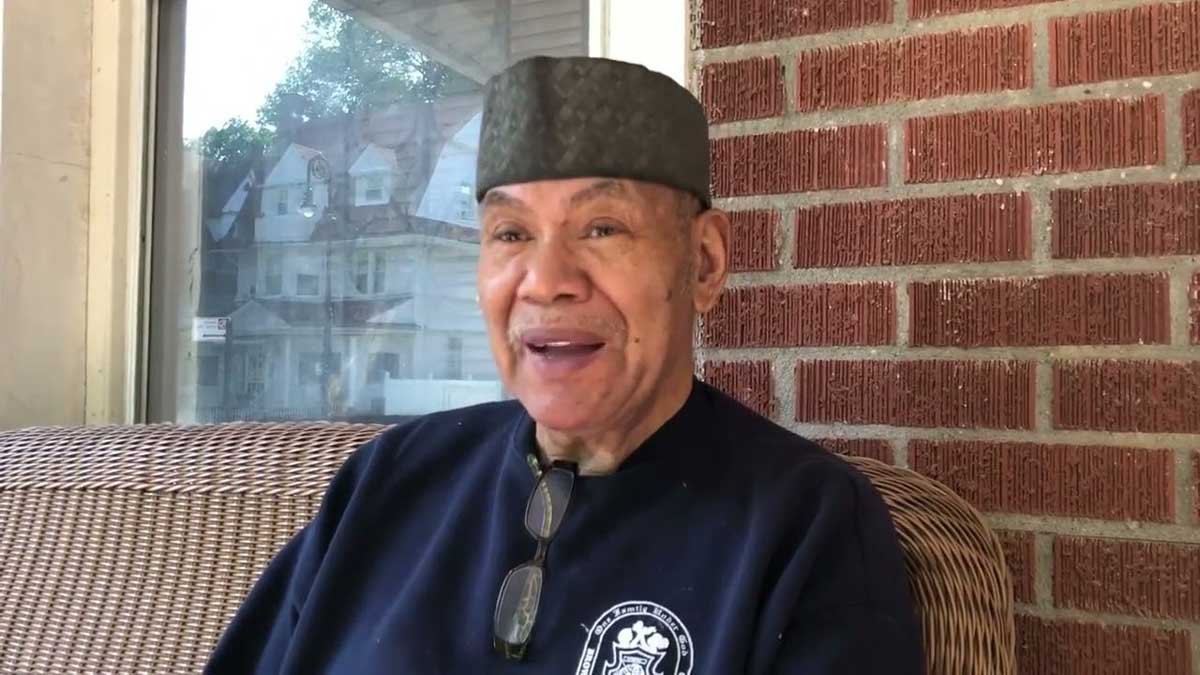

Minister Clemson Brown: “I’ve Always Been Looking for My Blackness.”

Basir Mchawi

Minister Clemson Brown was born in the backwoods of South Carolina during one of the worst periods of Jim Crow and racial segregation. Many would ask, ‘How is it possible to evolve from a cotton-picking sharecropper to an award-winning documentarian with over 20,000 hours of audio and video, detailing some of the most important events in the struggle of African People spanning at least forty years?’ Minister Brown’s answer would be twofold. First, he would say, ‘I come from a strong family.’ Then he would tell you, ‘I have always been looking for my Blackness.’

As the Brown family engaged in the post slavery business of sharecropping, the family was able to save money and buy land. As Minister Brown says, “No one gave us anything. We had to fight for everything we had.” At one point the family owned over 1,000 acres of forest and farmland in rural South Carolina. When Minister Brown’s father died, young Clemson was sent to live with an aunt in the South Bronx. At the age of twelve, Clemson had to confront the deep cultural differences between the rural South and urban North. “It was a real culture shock for me,” Minister Brown confessed. He went to Morris High School where his southern ways were not easily accepted. “I used to greet everyone I came into contact with and would attempt to shake hands with everybody.” Minister Brown’s classmates and neighbors saw his South Carolina ways as “country.” A saving grace was that the hard work of sharecropping had made young Clemson quick and strong. He became a pretty good athlete running track and boxing. It was through sports that Clemson started being liked by his South Bronx peers. His friendly demeanor and Southern charm helped as well.

In pursuing higher education, Clemson went to City College in Harlem. “I got involved in everything Black. I wanted to be in the African-centered movement because I saw the harm that white people could do to us,” said Brown. Some experiences in both the North and the South had convinced Clemson that there had to be a better way. As he got more involved in the African Liberation struggle he met luminaries like Dr Leonard Jeffries and Reverend Herbert Daughtry. Dr Jeffries, the founder of the important Black Studies program at City College, became an influence. The liberation theology of Reverend Daughtry attracted Brown and he was ordained as a minister at the House of the Lord Church in Brooklyn. “The House of the Lord became a meeting place for revolutionary groups from around the world,” he said. African Liberation movements and radical groups from all over the globe saw the House of the Lord Church as a safe place to meet and hold public events. Minister Brown, who started out with an 8 mm movie camera became the official documentarian for the local Black United Front and the National Black United Front (NBUF). At Reverend Daughtry’s urging, Minister Brown invested in new equipment better able to capture the history that was unfolding. He began filming local, national and international events. One of the historic events he captured as an NBUF member was a meeting of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in Kenya.

One Sunday while he was preaching at House of the Lord, when Reverend Daughtry was away on business, a visitor would change Minister Clemson Brown’s life. In the church sat Dr Yosef Ben-Jochannan, the famed historian and Egyptologist. After Minister Brown’s sermon, Doc Ben came to the front of the church, extended his hand to Brown and whispered, “Why don’t you stop lying to these people. Come to Egypt!” Minster Brown was stunned but he responded to Doc Ben’s challenge. Brown says, “I owe Dr. Ben a lot. He changed my understanding of religion and Christianity.” For the next decade, Minister Brown traveled to Egypt with Dr. Ben’s groups, absorbing everything and filming as much as he could. Later, Minister Brown became the documentarian for the United African Movement (UAM) and was a fixture at the Slave Theater on Fulton Street in Brooklyn. The Slave Theater became a focal point for meetings and programs in a manner similar to the House of the Lord Church and the Harriet Tubman school in Harlem.

To date, Minister Brown has digitized about 5,000 hours of video content. With thousands of hours of video still to be digitized, Minister Brown has a vision. “I want to open a multimedia museum in South Carolina. The South is key.” His work can be seen at the website www.tapvideo.com. TAP Video stands for Transatlantic Productions, Minister Brown’s company. You can go to the website to see some of Minister Clemson Brown’s important work and find ways to support his vision. As the Akan symbol of the Sankofa bird tells us, “It is not taboo to go back and fetch what we have forgotten.” In other words, we must go back to our roots in order to truly move forward. A museum in his South Carolina birthplace would be a fitting way for Minister Clemson Brown to close his Sankofa circle.

Basir Mchawi is an activist, educator and communicator. He can be heard on his award winning WBAI radio program, Education at the Crossroads, on Thursdays at 8 pm.